Interview with Motown Bassist Tony Newton

July 31, 2021

In preparation for my book on the history of the electric bass, I spoke to bassist Tony Newton about his experiences working for Motown in the 1960s. We discuss his early years playing bass around Detroit, his work as a touring musician, his recording in the studio alongside famed Motown bassist James Jamerson, and more.

Tony Newton, ca. mid-1960s

Brian F. Wright: In your book, Gold Thunder, you mention that you first got interested in the electric bass while playing saxophone in a local rock ‘n’ roll band. Do you remember why you were initially drawn to the instrument?

Tony Newton: Yeah. I was drawn to the instrument for the sound. First of all, I knew that [if I played bass], I would always be working. Because rhythm players get hired before saxophone players, and there weren’t that many electric basses around Detroit at that time. I also just loved what was going on with the instrument on the recordings that I had been listening to. I just loved the instrument, like I said in the book.

BW: And you were around 14 or 15 at that time?

TN: 14.

BW: Was your first bass a Fender Precision?

TN: Well my first bass was a red solidbody Epiphone [likely an Epiphone Newport]. It sounded pretty good, but it was a cheap bass. So it was something to learn on but that’s about it. At that time, I knew everybody was playing P-Basses, and so I had to get one.

BW: So how long was it do you think before you started gigging regularly on bass?

TN: It was immediately. I was playing with John Lee Hooker. I played both saxophone and bass with him. It only took me a couple of weeks to learn the instrument because I had been playing all of the woodwind instruments, so it was no big thing for me to learn another instrument.

BW: And so, your first gigs on bass were in blues clubs around Detroit? And that’s how you got hooked up with John Lee Hooker?

TN: I played with all the blues guys. John Lee Hooker. T-Bone Walker. B.B. King. Because all the blues guys came from Chicago to Detroit because it was close. John Lee actually lived there. Plus, at that time, in the early sixties it seemed like you could find a different live music club every 10 blocks. When I left home to become independent, playing bass was my way of making a living.

BW: So were you touring regionally in the Chicago-Detroit area?

TN: I was in a band called the Ohio Housebreakers, and we did tour around in the car and that was the early part of the sixties. But I wouldn't call them tours, really, we just did gigs outside of Detroit. They weren't that far. We’d just drive to them. We used to play in upper Michigan and things like that.

BW: And it was on a blues gig in Detroit that you were scouted for Motown?

TN: Yeah. [Motown producer] Hank Cosby heard me playing in a club. Well everybody in Detroit at that time wanted to get with Motown because we heard they were looking for people, and it was just exploding. But I didn't really have any connections, except one, which was David Ruffin, because he and I were playing in the same band together.

BW: Was that The Jaywalkers?

TN: Yeah, that's it. And so he got with the Temptations before I got with Motown, but then there was another friend of mine Cornelius Grant, the guitarist for the Temptations, he was the first one in there, then David went in, and then I got in.

Newton (far right) and David Ruffin (second from left) in the Jaywalkers

BW: And so, when you first became a part of Motown, it was specifically working as a touring musician?

TN: Yes. To replace Jamerson on the road with Smokey Robinson.

BW: The idea was that Jamerson was more valuable in the studio, and so they hired you to be a touring bassist?

TN: Yes.

BW: When you were on the road with the Miracles for that first tour, were these package tours where you're playing alongside a bunch of other acts or…?

TN: See, you really have to separate those tours from the [later] Motown tours. The Motown tours were package acts, but Smokey’s was not. Smokey and the Miracles were probably the least working act at Motown because Smokey was Vice President. But it didn't matter because I got paid either way. I was on salary.

BW: You were on retainer? Do you remember how much you were paid?

TN: Around $250 per week. Back then that was good money.

BW: For those early Miracles tours, do you remember how you travelled. Were you on a bus, did you have a car?

TN: We were always in a car. We had a station wagon. And the Miracles flew to the gigs and the musicians would drive. And we had a driver and we put all of the equipment in the car. Like if we were going to play the Apollo, because we played the Apollo quite a bit. I don’t know if you know this, but a lot of people think the Apollo was the only theater like that, when that’s far from the truth. You had the Apollo in Harlem, the Brooklyn Fox, the Howard Theater in Washington, the Uptown Theater in Philadelphia, the Fox Theatre in Detroit…

BW: Do you remember playing mostly to black audiences back then?

TN: Yes and no. We played lots and lots of colleges. So it was a mix. There were some black gigs and some white gigs. Because the white venues probably had more money to pay the Miracles, so we sometimes played more white gigs then we did black gigs.

BW: Do you remember what kind of bass gear you were using on the road back then?

TN: I was still using a P-Bass. For amps, I got endorsed by Ampeg. Initially I played a B-15. Now I’m the only player that I know of, besides Jamerson, who played the b-15 with an extension. I had two cabinets.

BW: And that gave you a louder sound, compared to other people at that time?

TN: Exactly. Well it’s a Motown Sound, right?

BW: So, just to clarify: you’re in the station wagon, you have a gig at the Apollo, Smokey and the Miracles are going to fly in. Is it you and Marv Tarplin in the car?

TN: Right. We’re in the station wagon and they would pick us up the night before because it usually took 10 hours, I think, to get to New York from Detroit. Each of those theater gigs were anywhere from a week to 10 days because there’d be about 10 acts on each show.

BW: So you would do kind of a residency, where you'd stay for multiple nights at the Apollo and multiple nights at the other theaters?

TN: Yeah. About a week to 10 days. And there’d be 3-4 shows every day.

BW: And so you'd have these kind of week-long residencies at the big theaters and then in-between you would play college dates and other, small gigs?

TN: Yeah, we’d have other dates. Right.

BW: Do you remember how you prepared for the tour?

TN: There wasn’t much preparation really. Sometimes we would rehearse if they wanted to do new songs. Like they wanted to do “The Best is Yet to Come.” But we didn’t do that all the time. Originally, we rehearsed in Detroit before we went out, probably five or six times

BW: Do you remember how you learned the tunes? Did you study the records, did you just learn them during rehearsal?

TN: Both. Because I wanted to make it sound as authentic as possible, so I studied Jamerson’s bass lines and I could read.

BW: So, you were looking at transcriptions where someone had written down Jamerson’s parts?

TN: Yes. You weren’t going to get with Motown unless you could read music. So I memorized them.

Motortown Revue in Paris LP, recorded April 13, 1965

BW: When you were playing live, did you try to recreate those Jamerson bass lines exactly as they were on record?

TN: Yes. Well, I still have to be myself, right? But, at the same time, I was young, and I was just trying to duplicate Jamerson. I’m still me though. You can hear me playing live on the Motortown Revue in Paris album [from 1965].

BW: Was it hard to recreate the “Motown Sound” live?

TN: No. Not with the right people. And that’s why I had two cabinets, so the bass would stand out. But we never had a problem. Marv Tarplin had an original sound, and he was on all the records, and so we never had a problem with the mix on stage. And out road manager would always go out into the audience and deal with whoever was dealing with the sound.

BW: What was it like going on a national tour like this when you're a teenager? Was it exciting? Was it grueling?

TN: Both. [Laughs] It was both exciting and grueling. But it wasn't that grueling, you know, because if it was too grueling then it wears you out and you can't be good for the shows. So there was always time to rest up. There were never any times where I was too tired to play a show or wore out from traveling or anything like that.

BW: Compared to a lot of other bands that were doing strings of one-nighters, it seems like you guys had a bit more stability.

TN: Yeah. We did one-nighters but they were spaced out. I think the most we ever did was maybe 10 one-nighters in a row.

BW: On this first tour with the Miracles, you ended up appearing in The T.A.M.I. Show concert film (1964). What do you remember about that?

TN: What I remember from the T.A.M.I. Show… The first thing I remember is [Rolling Stones drummer] Charlie Watts kicking over his bass drum after they finished playing. I hadn't seen a lot of rock groups and that was my first taste of the British rock experience, so it was very exciting, even though it was just another gig for me.

The Miracles performing on the T.A.M.I. Show (1964). Newton is visible in the upper right at the start of the clip.

Newton and the Rolling Stones backstage at the T.A.M.I. Show

BW: Did you think it was silly, him kicking over the drum? Or was it exciting?

TN: I’m still baffled. [Laughs] Because after they finished playing a song, he just kicks over the drum. And I never saw anybody do anything like that. But they could do it because they were independent artists and they could do what they wanted. So it was more interesting… Like now here we are how many years later and that still sticks out in my mind more than anything else.

BW: So your first work in the studio for Motown comes in early 1965, when you're 16?

TN: Right. Holland-Dozier-Holland wanted two basses and three guitars.

BW: Did they ever give you a sense of why they wanted two bass players or what they were going for?

TN: Well, they just wanted something innovative, something that wasn't the norm. And so, [on the sessions] Jamerson told me what to play. I’d usually play the high part and he would play the low part. You can hear it on “Stop! In the Name of Love,” “Nowhere to Run,” and “Reach Out.” You can hear the two bass parts if you listen closely.

BW: So you had heard of Jamerson at that point, but had you met him before you went into the studio?

TN: Oh yeah. Because he was playing around town. The Funk Brothers were playing jazz around Detroit all the time. They’d be doing the studio during the day and some nights, and when they weren't playing in the studio, then they were playing clubs.

BW: What were your first impressions of him?

TN: Well, he was a phenomenal player, you know, and he still is. I mean to this day his work is unparalleled. Because if you listen closely—and this is something no bass player has achieved in life yet as far as I'm concerned—you don't hear him repeating anything between all of the acts. Each artist he gave them their own sound. That is what impressed me the most. He does not play the same with the Supremes as he does with Martha and the Vandellas, or the Marvelettes, or the Four Tops, or the Temptations, or Stevie [Wonder]. Every one is different. He plays a different way. That's why Berry Gordy hired him because he was a genius on the bass.

There was a place in Detroit called the Graystone Ballroom and James Brown, the Isley Brothers, all the big acts would come through there. So there was a Motown Revue that played there just as Motown was breaking out and that was the first time I ever saw Jamerson play. And he had one cabinet on stage and another one underneath the stage! It blew my mind. He was using that cabinet underneath the stage as a resonator, and I’d never seen anyone do anything like that. The whole stage became a bass cabinet at that point. So that's how I knew I had to have that extension cabinet.

Jamerson’s and Newton’s names listed side-by-side on a Motown session contract

BW: Based on the contracts I’ve found, you and Jamerson played together on “Stop! In the Name of Love” and “Nowhere to Run” [contract dated January 22, 1965], “Love is Like an Itching in My Heart” [contract dated June 24, 1965], and “Reach Out I’ll Be There” [contract dated July 8, 1966]. Do you remember any of these sessions specifically?

TN: All of them. I remember all of them. I was just thrilled to be in there. I was just in there doing whatever they wanted me to do so I could stay in there. I was doing my best and I know they wouldn’t have had me in there unless I could handle it. Say, for example, on “Nowhere to Run,” Jamerson told me to play in the upper register on the G-string, while he’s taking the low part.

BW: So, for the most part you were playing more foundation, groove stuff while he's playing more melodic stuff on top?

TN: More intricate. More intricate lines, I would say. Because when you listen to them, do you hear two basses? It’s locked. We are so locked that most people don't even hear two basses. You have to listen very, very, very closely and have the awareness that there are two basses. Because we are so locked together that it sounds like one instrument.

BW: So Jamerson would tell you what to play?

TN: He’d direct me. Yes. He’d tell me what to play. He’d make up both our lines on the spot, like he did all the time.

BW: The records from the Musician’s Union show that you were paid $61 per three-hour session. Does that sound right?

TN: If you say so. I think I remember $120 eventually. It went up. By the time I left Motown, it was $120.

BW: So that money was in addition to that $250-per-week salary you were getting for playing with the Miracles?

TN: Yeah.

BW: Did that feel like good money at that time?

TN: Oh it was good money. I bought my first house when I was 17. The House was only $10,000, but it was a good house. It was bungalow, two bedrooms. The money was good as far as I was concerned. It wasn’t the money that the Miracles were making. [Laughs] But it was good musician money and it was consistent. And those were not the only sessions that I was playing. I played on some Stax records and at United Sound [Systems]. We were talking about how there were so many clubs in Detroit, but it seemed like there was just as many studios. They were all over the place, trying to be like Motown.

BW: So, when it came to recording, you weren't signed to an exclusive contract with Motown?

TN: Yeah. I was independent.

BW: You’ve said that after you started recording for Motown, you and Jamerson became friends, and he would stop by your house to hang out and show you some stuff on the bass? Do you remember any of the specific lessons you learned from him?

TN: He wouldn’t show me too much. He would hold back. [Laughs] He lived down the street from me. And he was inebriated a lot of these times. So, he just stopped by because we were close. The lesson that stuck with me, more than anything else, was he said, “The shortest distance to the next note is always the best.” That’s what he learned from playing upright, to play within the position. There's no jumping and that type of stuff.

BW: When people talk about Jamerson today, they kind of tell it like a tragic story. He died young and had problems with alcohol, and he died in obscurity.

TN: Where he screwed up was when he moved to California. First of all, you have to keep in mind that he was the best and everybody wanted Jamerson. So he could come into a session inebriated or drunk even and get away with it. So in Detroit he had no problem, they would hire him and they wouldn’t care. As long as he was playing, they wanted him there. But out in California there’s too much competition and you can't be doing that. That's what destroyed his reputation, because he showed up for a couple of sessions inebriated and the word got around and then they wouldn't hire him anymore.

BW: In 1965 you toured Europe as the bass player for the Motortown Revue, performing as a version of the Funk Brothers with Earl Van Dyke and Jack Ashford and backing up Martha and the Vandellas, the Miracles, Stevie Wonder, and the Supremes. Was this, again, another way to keep Jamerson in the studio and send you on the road in his place?

TN: Yes.

The Temptations, The Miracles, Stevie Wonder, Martha and the Vandellas, and The Supremes on the 1965 Tamla-Motown UK Tour (Newton is at the top right)

BW: Was this the first time you supported Motown acts besides the Miracles on tour?

TN: No. It was the first time I got to play with Stevie, but I had done some tours with Marvin [Gaye]. I would go out with other acts when Smokey wasn’t working.

BW: But those were just short tours here and there?

TN: Yeah.

BW: For that European tour, Mary Wilson [of the Supremes] remembered that tour as a bit of a disappointment.

TN: The crowds weren’t as big as they wanted them to be. They expected all of the places to be packed. Some of them were packed, but some of them were maybe half full. I guess enough people there hadn't heard about Motown yet, it was still getting exposed over there. It was a great tour as far as I was concerned, but I’m a musician. I thought the band sounded good.

BW: In the middle of that tour that you appeared in a famous episode of the UK pop show Ready, Steady, Go alongside Dusty Springfield. Do you have any particular memories of recording it? Was that the first time you had to mime along to a backing track?

TN: For the TV show, that’s what happened. Because you couldn’t count on the TV engineers to get the right sound. It always happens when it comes to TV, those guys don’t have an ear for live music.

1965 Ready, Steady, Go Motown Special (Newton can be seen at 26:05)

BW: That Ready, Steady, Go performance is often described as kind of the UK’s introduction to Motown. But the problem with that for you is that the show didn’t air until after you all had already come home.

TN: Yeah. That's the problem. Exactly. So what good is that, right? But it still helped Motown overall.

BW: So why did you end up leaving Motown?

TN: I was young and cocky because I thought I was the best and there weren’t many other bass players around that could play in the Motown style and read music…

BW: You tell a story in the book about a run in you had with Berry Gordy on that European tour.

TN: Right. So we’re on that tour and Smokey is on stage and I’m doing my usual thing. Berry tells one of his flunkies to tell me to turn down. Well I worked for Smokey and if Smokey isn’t turning around to tell me to turn down, then I’m not turning down. Then Berry sends this guy on stage to try to turn down my amp, so I lift up my bass like I was going to hit him with it. [Laughs] So after the show, Berry says, “Get rid of him. Send him back home.” But Smokey said, “We can’t do that. There ain’t nobody around here that can play this music.” So that ended that, and I did the rest of the tour. And we worked it out.

BW: Well, in some ways, it was kind of like what Jamerson was doing. Where it was such a specialized skill set that you were allowed to get away with acting up a little bit.

TN: Exactly. And I knew it! [Laughs]

BW: So after Holland-Dozier-Holland split with Motown in 1968, you left to join them?

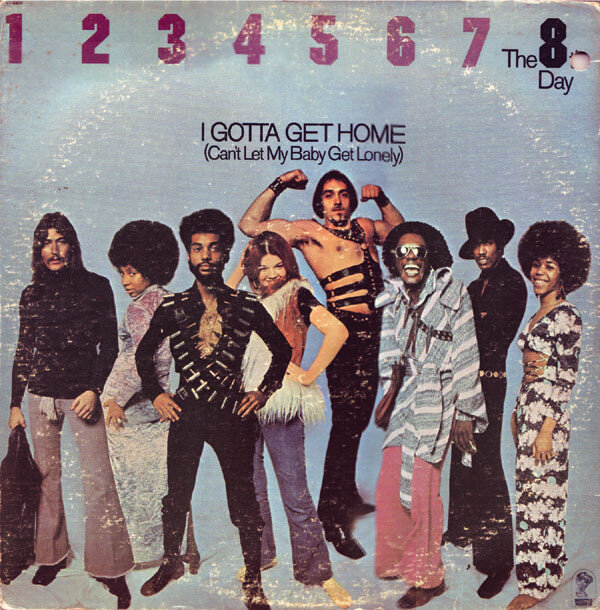

TN: It wasn't like that. There was problem with me and the Miracles at that time. I didn’t have the experience to write charts. And so they started hiring other people. It was okay until we got to one music director who didn’t like it if I talked back. He didn’t like that, so he got them to fire me. And so it was about time for me to leave anyway. Holland-Dozier-Holland had left already and they wanted me and so they got in touch. They gave me a real chance, because I played on the sessions and had my own group, the 8th Day. That wasn’t ever going to happen at Motown.

BW: When you joined them, was the idea that you might become an artist already on the table or did that develop later?

TN: It developed after I got there. The way Holland-Dozier-Holland worked was they would record tracks and have different artists sing on them. Then they would release certain ones. They called it the 8th Day, but there was no group.

BW: And that’s how “You’ve Got to Crawl” (1971) came about?

TN: Right. So that’s when my career as an artist took off.

BW: And by the time Motown left Detroit in 1972, it had been a long time since you worked for them?

TN: Right. And I’m glad. It was divine providence that everything happened for me. I mean… you leave a sign on the door saying “no more work here” when all of these people have made you rich? And you’re going to treat them like that?

BW: It’s cold.

TN: Really cold. Just because you want to be a Hollywood movie producer, now you’re going to just drop the music and drop everybody that put you where you are.

BW: When it comes to Holland-Dozier-Holland’s Invictus Records and Hot Wax Records, do you have a sense of how long you were with them?

TN: Maybe three years.

BW: Like 1969-1972, or so?

TN: Yeah. That sounds right. And from ’72 to ’75, I was doing my own thing as an artist. I formed a couple of groups and went more over to the artist side then.

BW: But you were still doing sessions?

TN: I’m always doing sessions, because that’s my bread-and-butter money.

BW: And you had moved to LA?

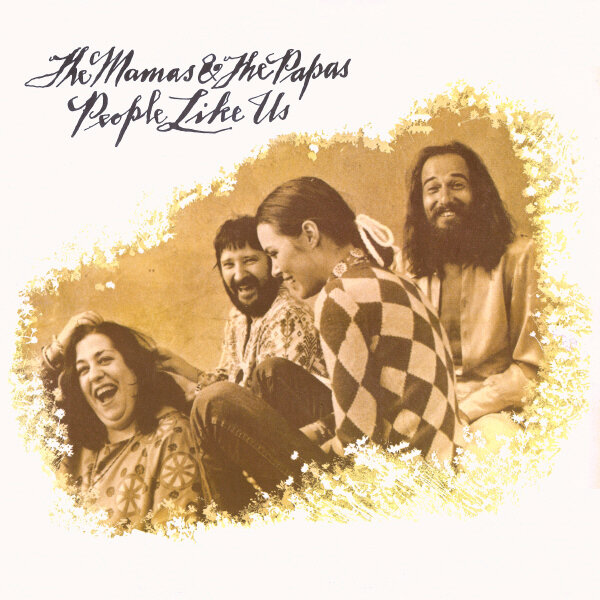

TN: Yeah. When I got to LA… First, I got plugged into [the session scene] through Gene Page, who had worked for Motown. He’s the one that got me paid triple scale and got me playing on sessions, like that final Mamas and the Papas album [People Like Us]. So my name got around town and I started playing all kinds of dates when I moved here.

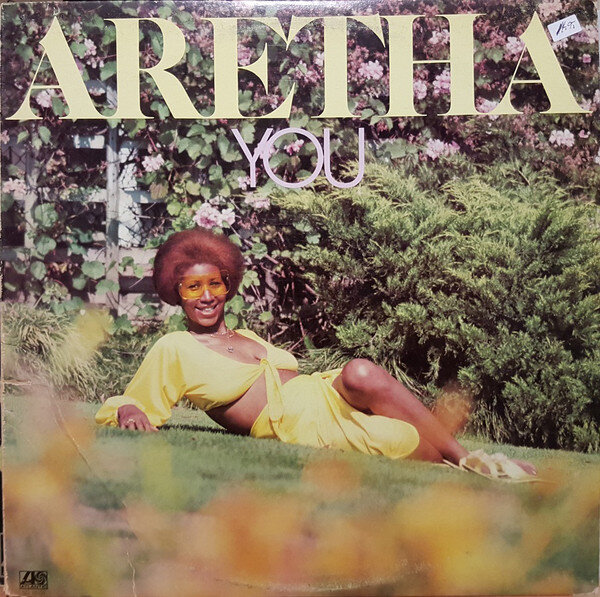

BW: That’s how you ended up on Aretha Franklin’s You (1975)?

TN: Yes. Right.

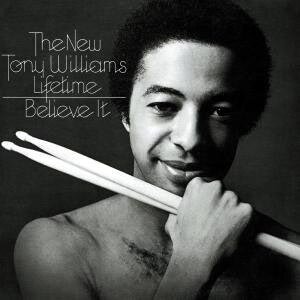

BW: And while you’re in LA, that’s when you hooked up with Tony Williams?

TN: Well, I called [jazz bassist] Michael Henderson. We were both from Detroit. I called him up and told him I was looking to get into a group. The session thing was fine, but I still wanted to do my own thing. He told me that Tony Williams had been trying out cats like Jaco [Pastorius] and Jeff Berlin for the Lifetime. So he put me in touch with Tony and I sent him a cassette of me playing. They flew me into New York and I got the gig.

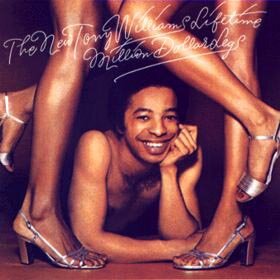

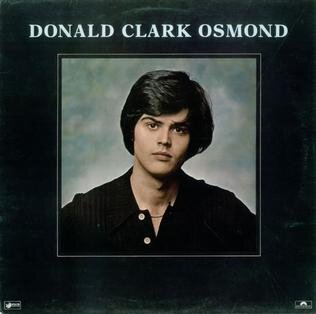

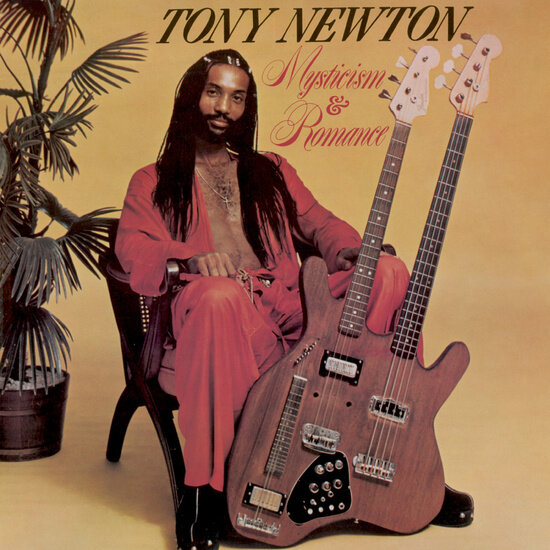

Selection of Albums That Newton Appears On

BW: If you look at your credits back-to-back, it’s a pretty diverse range of music. Do you see the Motown/Jamerson bass style as a foundation that you built on to play in all these styles?

TN: No doubt. No doubt. I couldn’t have done what I did if I didn’t have that foundation. It's a strange thing. I think hearing Jamerson playing different ways for different groups… I wasn’t conscious of that [at the time], but unconsciously it did seep in. And musically, I knew and understood that each artist has their own path and their own music. So I kind of molded myself to each session that I played on and that worked out for me. I honor and respect everybody's own unique creative expression and path and I try to tune into that direction, because that's the magic zone that you can get into where the hits happen. You have to get all the way into the music and not have any barriers or mental concepts about what the music is “supposed” to be, as opposed to what it can be.

BW: I know that you weren't included in the Standing in the Shadows of Motown movie (2002)…

TN: Let’s talk about that movie. They weren’t interested in accuracy. They should have had both Bob Babbitt and myself in the film. Because I was there for longer than Babbitt was. When I was growing up, it was Jamerson and Babbitt that doing all of the sessions in town. Then I came on the scene. But Babbitt didn’t tour with nobody at Motown. He toured with [artists from] Golden World [Studio], but that was another label. He did play on some sessions but you can tell a difference between the way the three of us play. We played in similar styles, but not the same. I'm a busier player than both of them.

BW: After the film came out, you did get to hook up again with Jack Ashford, right? So was that sort of a silver lining?

TN: Oh, yeah. I got to tour with the Funk Brothers. Jack is still living, but I’m still the youngest Funk Brother, and it’s only the two of us left living.

BW: You’ve had a long career, and that’s probably given you a broader perspective than you might have had in the sixties. Looking back on it now, how do you feel about Motown? Did you feel like the company treated you well?

TN: Let me put it this way. They did not treat the musicians as they should have. They were all “work for hire.” They could have been paid more because Motown was making enough money. I understand what Berry was doing, but like I said, when he put that sign on the door, it really showed you where his head was at. He really didn’t care about anybody else but himself. But Smokey is one of the best human beings I’ve ever met in life. So that’s who my relationship was with. And I still cherish it to this day. So I am grateful for my work and the relationships I had there because it built the foundation for my whole life.

Behind every great artist is an even greater teacher and so that’s where Jamerson and all these other people come in. All these associations. I couldn’t be where I’m at had I not learned from them.

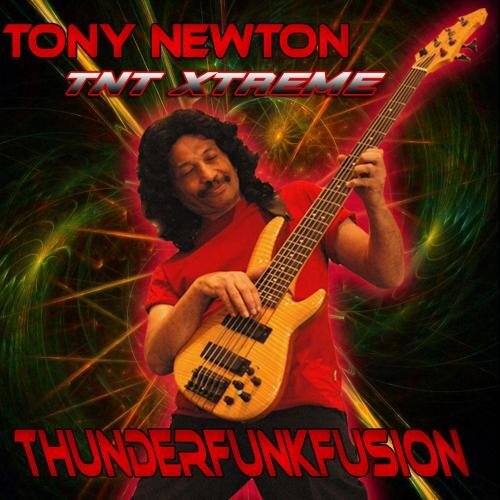

Tony Newton today

Trailer for Tony Newton: Groovemonster

Tony Newton’s Website: https://tonynewtonmusic.com/

Tony Newton’s YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/c/antoniotonynewtonmusic